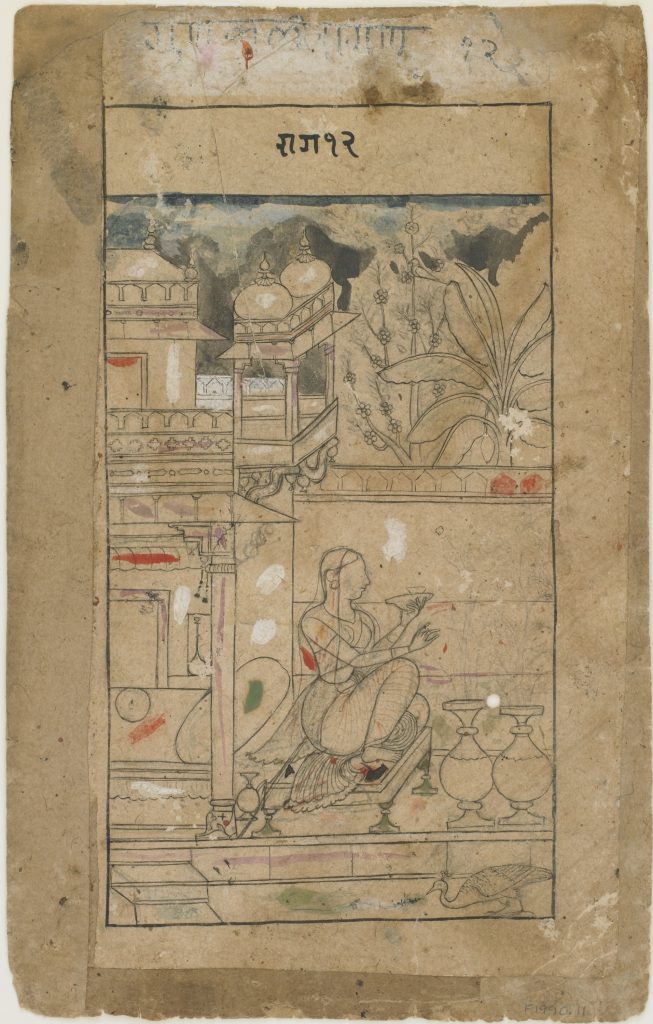

Gunakali Ragini

Gunakali Ragini

India, Rajasthan, Bundi, ca. 1680

Carbon black and opaque watercolor on paper

Courtesy the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1990.11

Ragamala paintings are a part of a tradition that entails intricate, vibrantly colorful brushwork, great expertise in organizing composition, and the mastery of many different techniques. The fine brushes required to achieve the intricate details required for outlining and coloring the paintings were made using only a few strands of hair. Each brush would only be used to apply a single color so as to not tarnish the vibrancy of the other colors. The initial sketch of a ragamala painting was made by the master who intentionally left room for a border around the drawing. Because ragamala paintings were held in the hands of viewers, the border protected the image from the wear and tear of handling.

Only natural materials were used: organic inks and dyes, conch shells, vegetable colors and minerals, including precious stones, pure gold, silver, zinc, and lead.

The handmade papers used for Indian court paintings are traditionally crafted from cotton. Multiple sheets are stacked and then coated with a layer of white pigment. This coating guarantees a smooth enamel-like surface. After the painting surface had been prepared, specialists would begin to make the color pigments. There are three steps in the process to prepare a pigment from a hard mineral. First stone is ground by hand with mortar and pestle to create a fine powder. This is then separated in a progression of washes to expel any added substances and pollutions that would diminish the shade’s brilliance. Then came the essential step of binding the pigment. This allowed the pigment to flow and stabilized the color. Gum Arabic, the crystallized sap of the babul tree, was the most commonly used binding agent. The pigments were then mixed together with the gum and water to create a smooth liquid paste. If any of the paste is not properly liquified, any small lumps could destroy the painting.

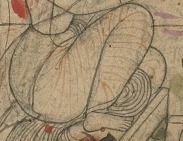

The artist used contour lines to draw the shape of the woman’s dress and the folds of the drapery, this attention to detail in the planning stage ensured that the finished product was graceful and balanced.