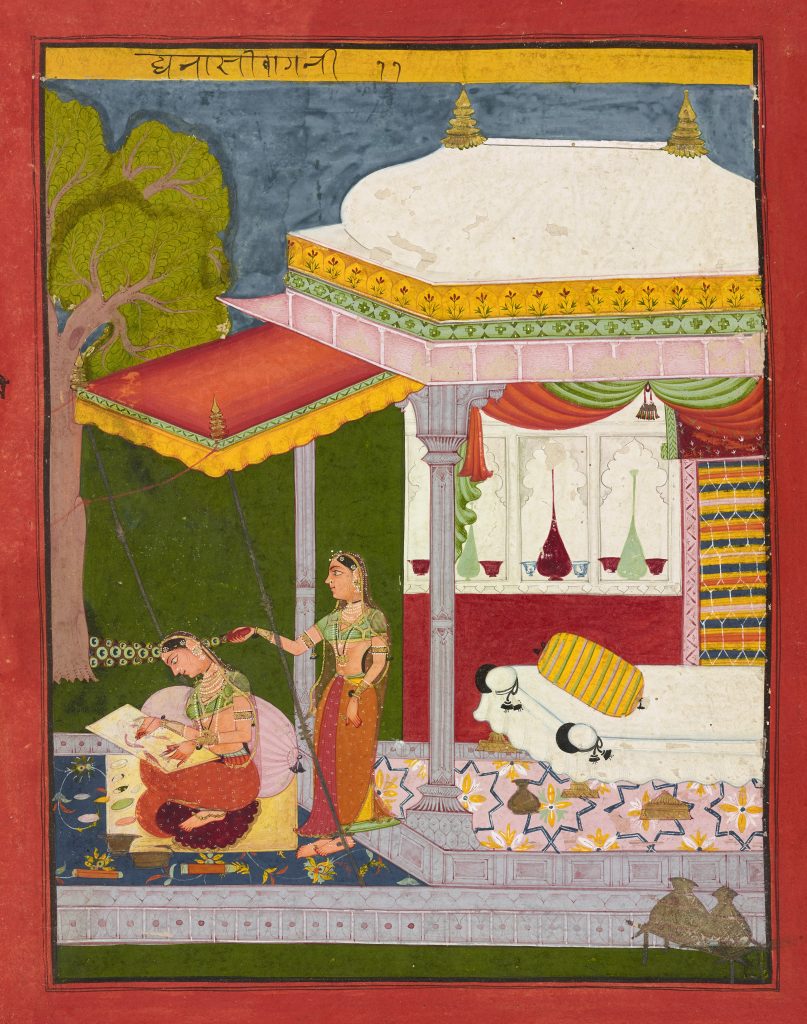

Dhanasri Ragini

Dhanasri Ragini

India, Rajasthan, Bundi or Raghogarh, ca. 1680

Opaque watercolor and gold on paper

Courtesy the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.: Purchase and partial gift from the Catherine and Ralph Benkaim Collection — funds provided by the Friends of the Freer and Sackler Galleries, S2018.1.32

In Dhanasri Ragini, the central emotion is love and the pain of separation. Here a heroine (nayika) and her female companion (sakhi) are outside a sandstone pavilion, shaded by a yellow and red canopy and framed by a deep green rectangular space. The composition is compartmentalized. The women occupy the exterior space. The interior space, a bedchamber, lies empty. Her lover is absent. A feeling of longing and loneliness pervade.

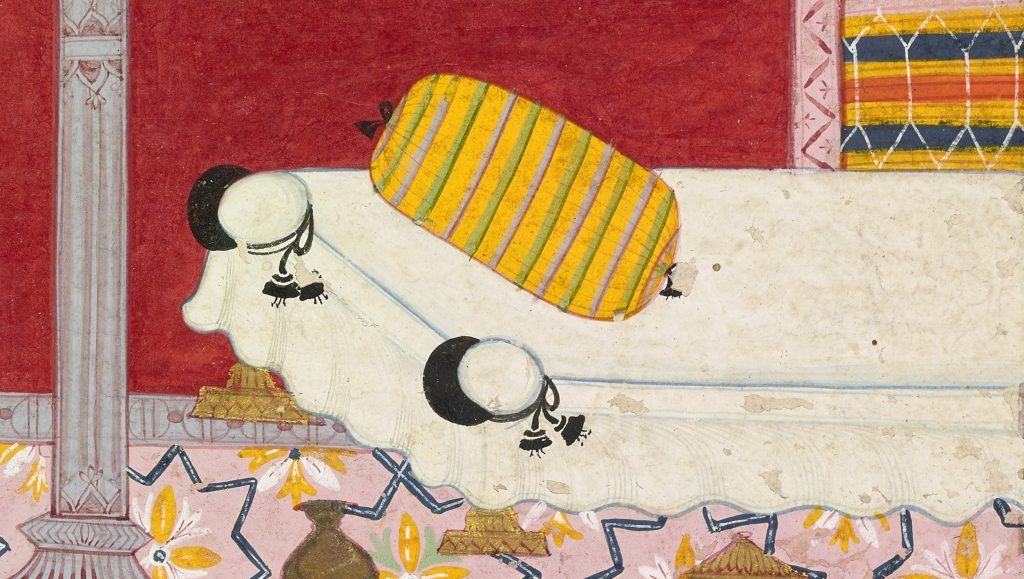

The drapes are pulled aside to reveal an elegantly, appointed bedchamber, but no one is there. Many ragamala paintings express longing by placing figures in separate compartments or sections of the painting. Here, our heroine is outside, and the empty bedchamber alludes to the absence of her beloved.

Painted around 1680 by an artist in Bundi or Raghogarh – small kingdoms in what is now the Indian state of Rajasthan – the painting shows a courtly setting in which a woman sits and paints an image of her beloved. Dhanasri Ragini is often indicated by a woman making a portrait of her beloved. Although female artists were not typically depicted, the subject was not implausible. Most court artists were highly trained men who worked as a part of a workshop, producing commissions for royal patrons. Often a family of artists would work for a ruling family exclusively.

The painting also provides a rare glimpse at how artists at that time worked. The drawing lines, visible on the heroine’s painting, are continuous and confident rather than sketchy and hesitant because artists had years of experience repeating the same subjects. Opaque watercolor paint was applied in thin transparent layers with a small brush over the line drawing. It was essential to paint thin layers and allow each to dry in between layers to achieve a luminous effect. It often took a team of artists to complete a work of art. An apprentice may grind the pigment and an upper level artist would add the delicate finishing touches. Fine details in gold (made from pulverized gold foil mixed with water) were applied last. The surface on which one painted was created of layers of paper, glued together to provide a stiff cardboard-like support. This prevented warping, which can be problematic in watercolor painting.

On the paper one can see an outline of a figure, which by convention is our heroine’s beloved. The heroine-artist is surrounded by the art supplies needed to create a watercolor painting: shells that contain pigments, a jar holding brushes and two bowls of water: one for cleaning and one to mix with pigments

Artists at the Rajput courts of Bundi and Raghogarh combined local elements with those from the imperial Mughal workshop. The rich color palette, the shape of the eyes, and the composition are typical of Rajput courts. Rajput style tended to be more abstract than naturalistic. However, Rajput artists adopted Mughal imagery, seen here in the naturalistically shaded drapes, architectural elements of the sandstone pavilion, the star patterned tile and the interior niches.