The enjoyment of ragamala painting was a cultivated and multisensory experience. In sumptuous royal palaces, the elite of India’s princely

states would gather in intimate settings, surrounded by food, wine,

and music, to share the experience of viewing paintings. Ragamala paintings were illustrated to accompany specific musical modes called ragas.

Both the paintings and their musical modes evoked specific moods (bhavas) and emotional responses (rasas). These small hand-held paintings were intentionally intricate and complex. They possessed fine details, such as delicately applied strands of gold, and held clever allusions with meaningful imagery; which could only be appreciated by a sophisticated observer, called a rasika.

The first known ragamala paintings appeared around 1475, decorating the margins of Hindu manuscripts with images of deities associated with the music. A century later, the paintings typically depicted human beings whose actions embodied the moods of musical modes. This art form grew in popularity and became a favorite of India’s aristocratic warrior class known as the Rajputs, as well as by the regionally-dominant Mughal Empire. By the 18th century, regional iconographic and thematic variations had developed and each Rajput state sponsored its own artistic practice.

Commissioning a ragamala was a sign of a patron's cultivated taste and refined pleasures. As patrons traveled with their beloved objects, regional styles and imagery began to merge. Ragamala paintings were widely popular in India only to decline in the 19th century with the rise of British rule and the loss of aristocratic patronage. However, the musical modes (raga) of Indian classical music remain popular into the present day.

Each raga is a musical mode that demands or excludes certain notes and then lets the musician improvise freely within those imposed limits. Over time the primary modes were classified as ragas and their sub-modes were termed as raginis. The music inspired music scholars, poets and painters who were moved to personify the modes, giving them visual form. These modes of music have existed for centuries and the names and classifications of the ragas vary considerably by region and time. This multiplicity defies easy categorization, but the variety is the natural outcome of an adaptive and inventive musical tradition.

Follow these links to listen to ragas performed as part of the Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art's music series podcast:

Yogic Sounds of India: K. Shridhar, sarod

North Indian Classical Music: Shujaat Khan, sitar

North Indian Classical Music: Vishwa Mohan Bhatt Part I

North Indian Classical Music: Vishwa Mohan Bhatt Part II

The Scent of Power

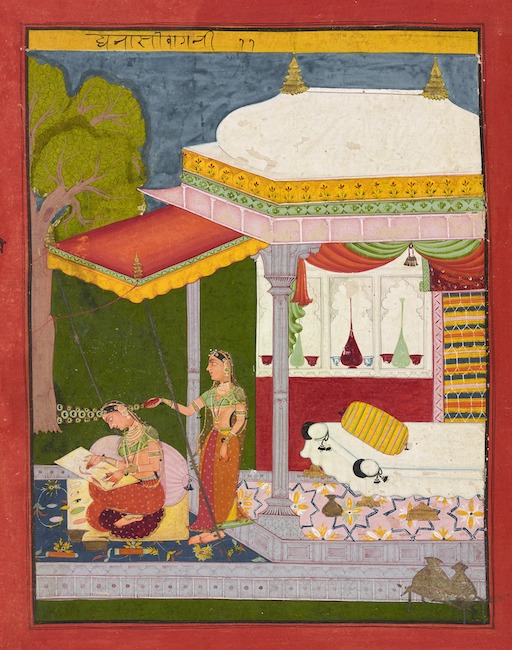

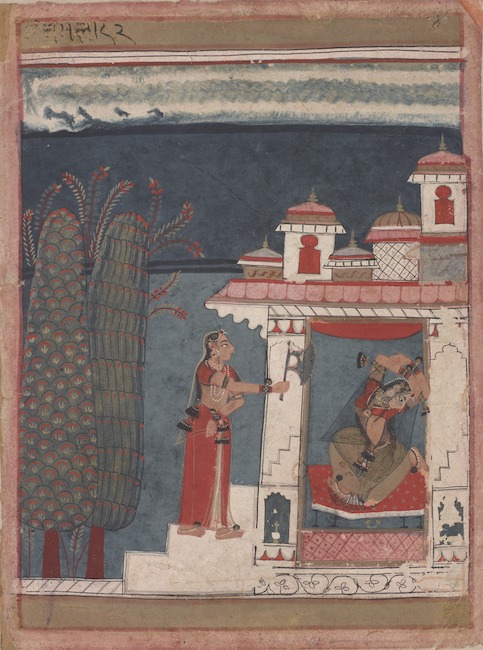

Drawing Her Attention

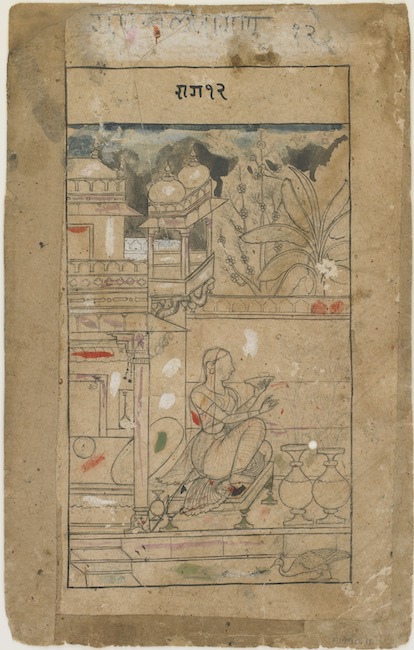

This painting within a painting provides a glimpse of artist practice. She sits and applies color to a contour line drawing on stiff paper. She is surrounded by seashells used as containers for pigments, a jar holding brushes, and two bowls of water for cleaning and mixing with pigments.

Although female artists were not the norm, the subject of this painting was not implausible. However, most artists were highly trained men who worked as a part of a court workshop, producing commissions for royal patrons.

Love as Emotion

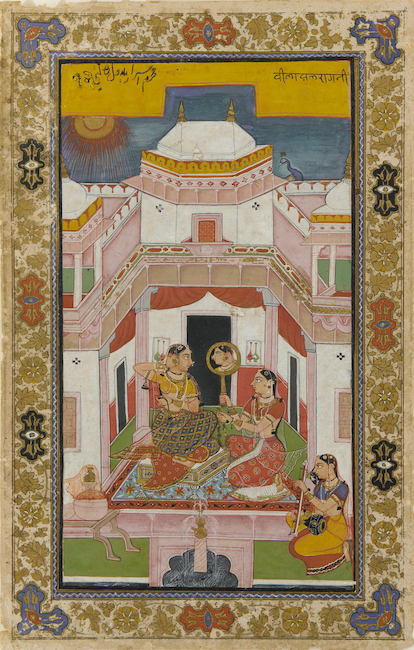

Ragamala paintings seek to inspire distinct emotional responses in the viewer. These emotional responses (rasa) can evoke love, mirth, sorrow, anger, energy, fear, disgust, astonishment, or tranquility. The ability to perceive, feel, and be immersed in an emotion is dependent on the sophistication of the audience. The feeling, or essence (rasa) of each mood is felt, or “tasted” by the connoisseur. One of the most common moods evoked by ragamala painting is the mood of love (shringara). This romantic mood often features three main characters: the hero (nayaka), the heroine (nayika), and the heroine’s confidante (sakhi). The role of the confidante, in most cases, is to comfort and guide the heroine until she can be reunited with her lover. The artists use distinct gestures (arched backs, yawning faces, bejeweled bodies, circling arms, or enlarged almond eyes) to represent a young couple’s love and passion. These examples are complemented by the artists’ use of color and ornamentation to evoke the feeling of romance.

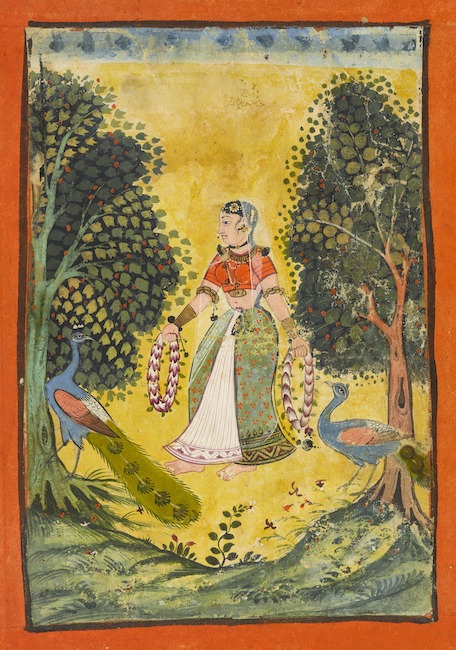

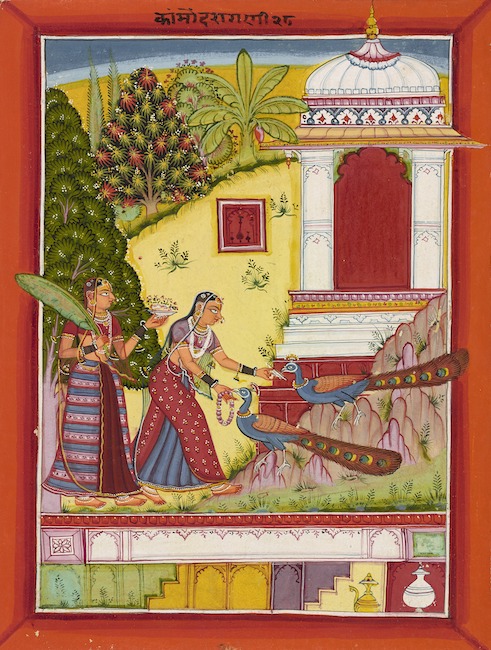

One common romantic scene depicts the heroine waiting for her lover in a secluded forest. In these scenes, key details emphasize the hero’s absence, such as paired animals surrounding the lone heroine. The paired animals next to the solitary heroine emphasize her plight. Many times, the mood of romance is heightened by specific times or seasons of the year. Several popular scenes depict lovers during the monsoon season, which is thought of as a highly romantic time of year. The season is highly anticipated, since it transforms the dry, arid climate into lush, green landscapes. These tumultuous storms halted military campaigns (sending soldiers home), and instead encouraged lovers to stay indoors together. It was also a time when many animals, most notably peacocks, took their mates. Certain times of day were also used to heighten the romantic mood of these paintings, such as the hours right before dawn. This was understood to be a particularly romantic time, as lovers were reluctant to part ways after a night spent together.

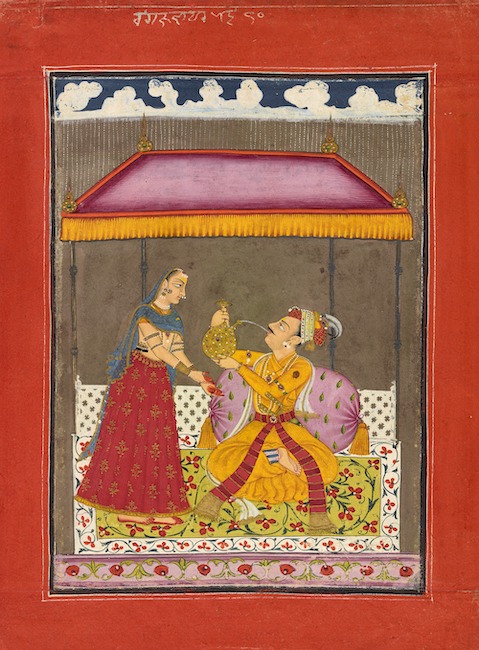

Quenching the Fires of Love

Five More Minutes

Love is in Bloom

Date Night

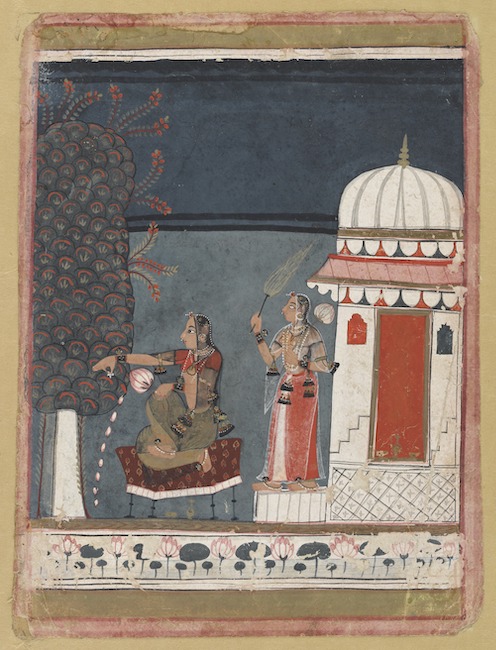

He Loves Me! He Loves Me Not!

Here, Malasri is pulling petals from a lotus. She plucks the petals in a deliberate manner as if to chant, “He loves me, he loves me not.”

The Heat of the Night

Love as Devotion

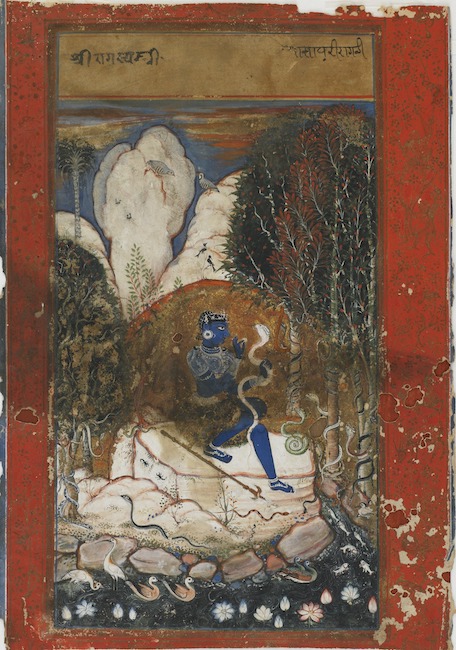

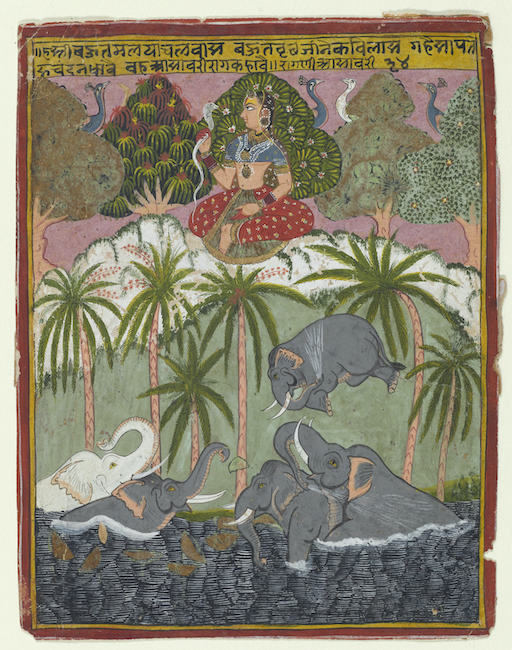

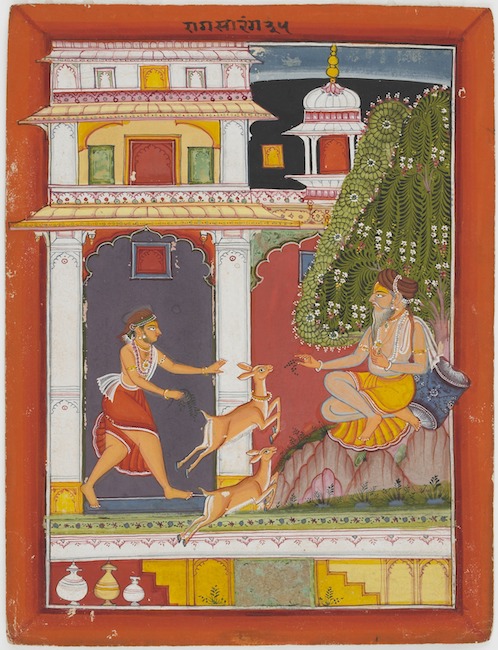

Ragamala paintings are intended to evoke a mood (bhava), which elicits a profound response in the viewer. Romantic themes are the most prominent moods in ragamala painting, but themes of sacred or religious devotion also conjure powerful emotions. Devotion in its many forms is an important part of the ragamala tradition, and artistic style, visual iconographies, and painting conventions all contribute to the creation of the sacred (shanta) mood in these devotional images. This mood is often indicated by a physical or metaphysical interaction between princely figures and a god, deity, or sacred person. At times these scenes contained intentional allusions to ragasassociated with romantic moods. This is because, in some Indian traditions, the loving devotion (bhakti) which is shown to a god, deity or sacred figure, is parallel to that shown to a lover.

One form of religious devotion is the practice of daily rites and rituals (puja) which can be conducted in a home or temple. While these rituals are depicted in some paintings, others reference spiritual enlightenment, at times visualized as divine beauty. These various depictions of sacred themes, encourage the viewer’s focused introspection. In fact, the immersive experience the viewer has with the paintings could be considered a sacred moment in itself.

The Divine and the Feline

Ornament of Shiva

Dangerous Woman

Beauty & The Beasts

Traditional Techniques

All ragas have a conventionally associated mood and iconography. However, artists varied greatly in their interpretation of the iconography based on both artistic preference and regional conventions. Stylistic variations that range from abstraction to naturalism, color palettes of jewel-like tones or gentle pastels, and a wide range of borders and framing conventions add remarkable diversity to ragamala paintings. Particular stylistic traits are often associated with specific courts and there is evidence to suggest that itinerant artists were capable of changing their style to match the tastes of local patrons. Naturalistic elements are often understood to be a result of contact with Mughal court painting traditions, whereas the vibrant color and simplicity of images is viewed as a descendant of Indic cultural traditions of wall painting. However, there is also evidence suggesting that artists would vary their style to suit the subject matter, employing abstraction for mythical or fanciful scenes and reserving naturalism for more historical subjects.

Artists were traditionally members of workshops in which they received their training. Some artists held hereditary positions in which they and their family worked within a single court for many generations. Other artists provided work for many patrons. Therefore, paintings are usually assigned to regions based on style and other cultural details, such as clothing. In all cases the artists trained in an apprentice system began by grinding paint and making brushes, before working their way up into roles that required a practiced hand and allowed for more creativity.

Fashionably Late

Lost Love

Work in Progress

Finishing Touches

What’s in a Name?

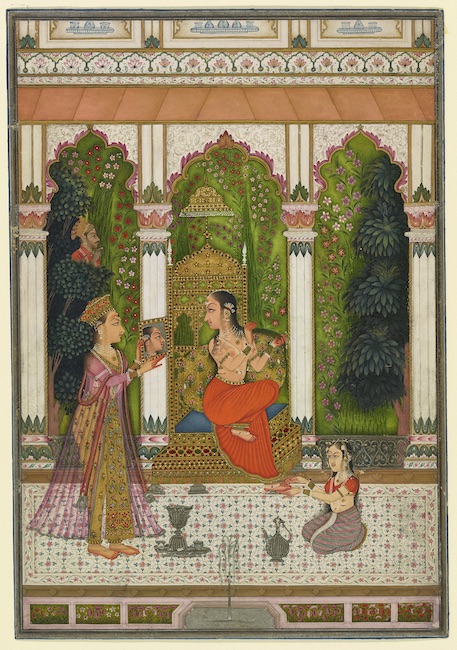

The Greeting

Architectural depth is shown by the overlapping of visual elements. The gazelle are the closest objects to the viewer as they overlap all other elements. The ascetic on the rock is on the same plane as the younger man and is therefore also in front of the building. Interestingly, the pavilion’s roof and senior man’s cushion overlap the frame creating a sense of the unreal.